The irrelevance of the main political axis of the 20th century

However, it seems to me that we’re moving towards a new configuration, dominated by different questions. The main reason for the change is probably that the left-wing parties to a large extent gave up on socialism after the fall of the Berlin Wall, followed by a general acceptance of globalisation by all mainstream parties, which again bred resentment when it failed to create prosperity for all.

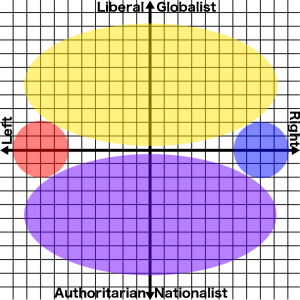

The country that demonstrates the new set-up best is probably France, where Macron’s En Marche and Le Pen’s Front National now are the leading political forces, supplemented by smaller left-wing and right-wing parties. It’s interesting Macron is called a centrist and Le Pen is characterised as far right, because they really aren’t that far apart on the old left/right axis, whereas they’re miles apart on the new axis. I think we might need new names that are as easy to relate to as left and right, but I’ve haven’t seen any good suggestions yet.

The SNP is also a decent example of a modern global-liberal party (it really isn’t a nationalist party in spite of its name, but simply a liberal pro-EU party that happens to be in favour of Scottish sovereignty), although Scotland as a whole hasn’t rearranged the political spectrum yet.

In England, it appears that the Tories under Theresa May are swallowing up UKIP and are becoming a proper authoritarian anti-globalisation party – it is interesting how the Tory manifesto is moving them strongly towards authoritarianism (e.g., ID cards and Internet censorship) and anti-globalisation (cutting immigration and preparing the country for a hard Brexit), while softening up on right-wing policies (increasing the minimum wage and capping energy prices). However, many right-wing liberals are probably still voting Tory, and the opposition hasn’t regrouped at all, which is why the Conservatives are likely to get an enormous majority. That wouldn’t be the case if they were facing a unified opposition along the lines of En Marche or the SNP.

I guess we shouldn’t be too surprised that major changes like this one can come about. In the 19th century, British political battles were between Whigs and Tories, and later between Liberals and Conservatives, and many of the biggest questions (like voting rights and free trade) were not easy to place on a left/right axis. The world is changing dramatically, so we shouldn’t be surprised if the fundamental political questions change, too.

It creates enormous problems for parties that don’t adjust to the new questions, but it’s also is a colossal opportunity for those that do.

I certainly recognise this world view. I haven’t thought in left/right terms for a number of years.

The SNP is definitely a progressive party and I’ve met many members who in previous years may have gravitated to the Labour or Green parties.

I feel very fortunate to have a natural home in the SNP. I do of course welcome the support we have from our colleagues in the Green Party. All the progressive parties need to work closely together to try and ensure the authoritarians don’t win.