Politics isn’t management

When Labour finally came to power last year, the sales pitch was simple: stability after chaos. Keir Starmer’s calm, managerial persona was held up as the antidote to the endless psychodrama of Johnson, Truss and Sunak. A lawyer rather than a showman; a civil servant in all but name.

When Labour finally came to power last year, the sales pitch was simple: stability after chaos. Keir Starmer’s calm, managerial persona was held up as the antidote to the endless psychodrama of Johnson, Truss and Sunak. A lawyer rather than a showman; a civil servant in all but name.

Twelve months on, that image lies in tatters. Far from being the sensible alternative to Tory mayhem, the Starmer government is rapidly acquiring its own reputation for scandal, drift and incoherence.

The Mandelson–Epstein debacle crystallised it. Appointing Peter Mandelson as ambassador to Washington, only to be blindsided by the inevitable revelations about his connections to Jeffrey Epstein, was the opposite of careful, orderly government. It suggested not caution but negligence – a government so inward-looking that it failed to spot reputational disaster until it was already splashed across the front pages.

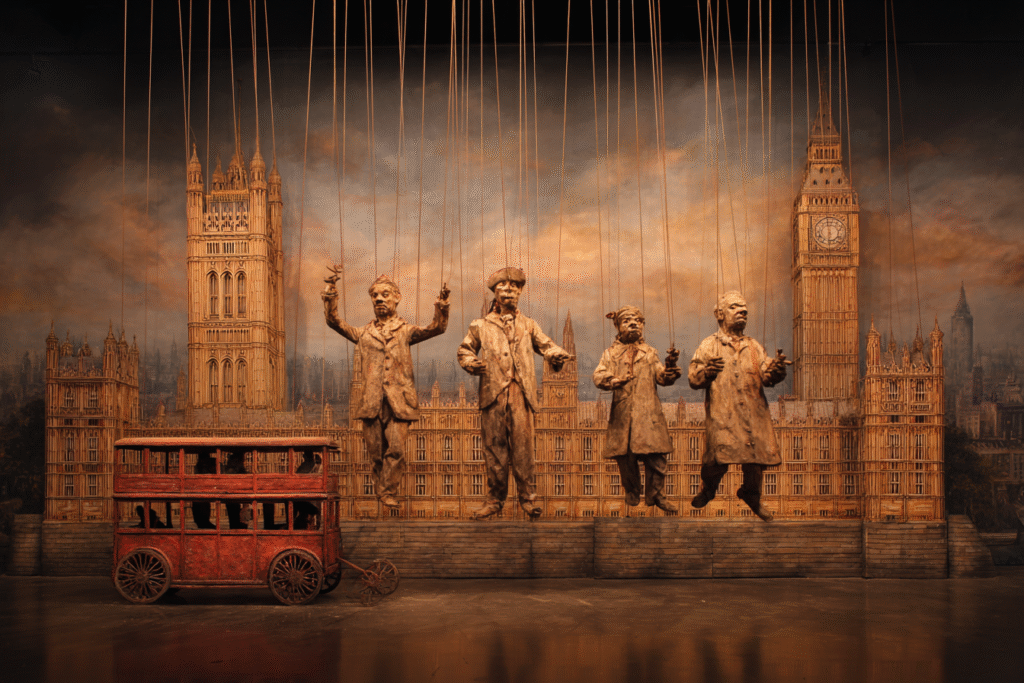

And then there is the question of who is really in charge. Increasingly, Westminster insiders talk about this as a McSweeney government more than a Starmer one. Morgan McSweeney, Starmer’s chief of staff and long-time strategist, is said to be the man pulling the strings. His network placed Starmer in the leadership, nurtured him, and crafted the message. The problem is obvious: McSweeney wanted a pliant frontman, and what he got was exactly that – a leader who does not lead.

It worked, for a time. Starmer’s unflashy hostility to Brexit gave him credibility with Labour’s pro-European members, while his lack of a strong ideological base reassured the machine that he could be steered. But governing is not opposition. A prime minister must persuade, inspire, and above all be seen to take decisions. Voters don’t listen to the backroom strategist; they look to the person at the podium. And Starmer, with all the charisma of a damp filing cabinet, cannot carry the story his handlers want told.

Now the trap is closing. Replace Starmer with another McSweeney-approved cipher, and the public will simply conclude that Labour is run by faceless operators. Elevate someone more charismatic and more rooted in the party’s traditions, and the machine itself risks being dismantled. Thus McSweeney and Starmer are locked together, mutually dependent yet increasingly poisonous to one another’s survival.

The irony is brutal. The very people who prided themselves on strategy have manoeuvred Labour into paralysis. Instead of stability, we have a government defined by weakness at the top, endless firefighting, and the sense that nobody is really in command.

The lesson is obvious, though unlikely to be learned: politics cannot be reduced to management. Voters want more than stability; they want to know who is leading them and why. Puppetry may deliver a quiet life in opposition, but in government it is exposed for what it is. And when the strings become visible, the audience stops believing in the play.