Green, Orange and Turquoise

Zack Polanski takes over the leadership of the Greens in England and Wales at a moment when British politics is more fluid than it has been in decades. If he wants to shape the coming years, he should think not just about policy and messaging but about geometry.

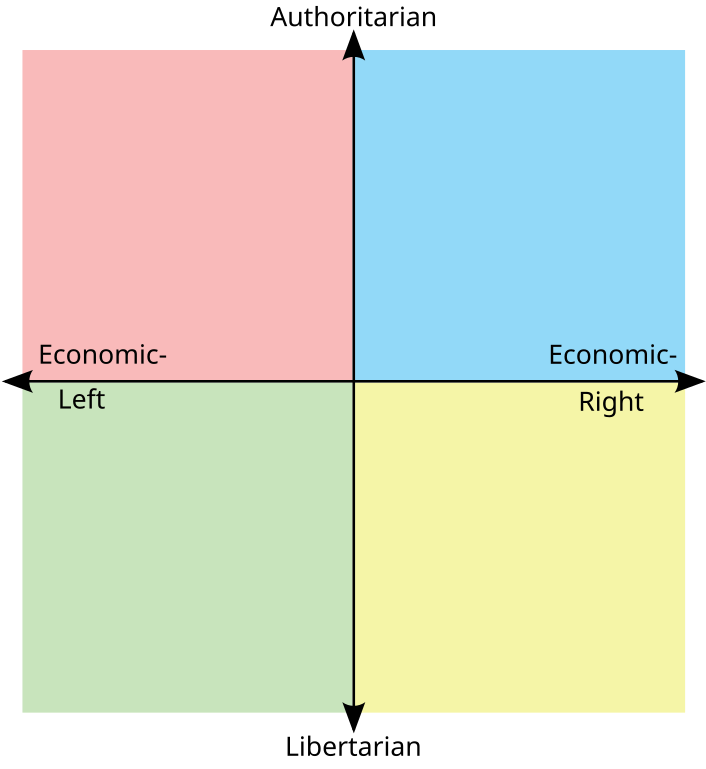

The standard left–right line is too cramped to explain what is happening. A better map is the Political Compass, which adds a vertical axis of liberty versus authority to the horizontal axis of economics.

For most of the postwar era, the Conservatives sat in the right-libertarian square (markets plus personal choice), while Labour settled in the left-authoritarian one (redistribution via a centralising state). That duopoly left the other two quadrants weak. Parties that tried to pitch themselves as left-libertarian or right-authoritarian were stuck on the margins.

Reform UK have upended this pattern by charging into the right-authoritarian corner. They now poll around 30 per cent, with projections ranging anywhere from 179 to over 400 MPs. Labour languish at 21 per cent, the Conservatives at 18 per cent, each on course for historic lows. Neither knows how to respond. Labour oscillates between echoing Reform’s toughness and promising managerial competence; the Conservatives cannot decide whether to mimic Farage or resist him. Both are trapped in neighbouring quadrants, offering only half-alternatives.

Here the compass matters. Under first-past-the-post, the most effective opposition does not come from the quadrant next door, but from the one opposite – the force that offers voters a full alternative, not a partial echo.

That opposite is left-libertarian. Fairness plus freedom. Ecological responsibility plus internationalism. A politics of dispersing power rather than hoarding it. This is the natural ground of the Greens and the Liberal Democrats. Both have shown they can entrench locally: the Greens with breakthroughs in Bristol, Herefordshire and Waveney Valley, the Lib Dems with their return across the southern shires and commuter belts.

The numbers make a pact tempting. Lib Dems poll at 14 per cent, Greens at nearly 9 per cent. Together that makes 23 per cent – more than Labour or the Tories. Under first-past-the-post, concentrated support could reward that with many more seats than they could ever hope to win separately.

It helps that Polanski himself knows both camps. Before joining the Greens in 2017, he was briefly a Liberal Democrat candidate in Camden and stood on their London Assembly list. That past does not bind him, but it does mean he understands the culture of both parties. If anyone is well placed to explore common ground between orange and green, it is their new leader.

There are objections, and they are real. The compass is a heuristic, not gospel; politics is messier. FPTP rewards concentration, not abstract positioning. Polls move. Both parties have traditions of “standing everywhere”. Yet the structural point remains: Reform’s rise into the right-authoritarian square creates an opening only the opposite quadrant can fill. Lib Dems and Greens are the parties that live there.

Scotland is a different case. The Scottish Greens are organisationally separate, the Lib Dems devolved, and most importantly independence defines politics. Any pact north of the border would require a shared stance on the Union, which does not exist. In England and Wales, where Reform threaten to dominate, the logic of cooperation is stark.

So here is the advice. If the new Green leader wants his party to be more than a conscience movement, he should reach across to the Lib Dems. A non-aggression pact in England and Wales – one candidate on each ballot, never both – could yield not just more seats, but recognition as the principal opposition to authoritarian populism. It would allow each party to concentrate on its strengths, and together they could claim the debates, the headlines and the role of genuine counterweight to Reform. Broadcasters would find it hard to ignore a bloc with support from roughly one in five voters, making debate exclusion much less likely.

When the dominant party claims one quadrant, the path to effective opposition runs through the opposite square. Reform’s turquoise surge points directly to orange and green.

Pingback: Make Our Nation Great Again-ism – Arc of Prosperity